by Lori Williams

AS SEEN IN

On the morning of his 12th birthday, Colson Rinella set out at dawn on his bicycle toward a gulch near his home in the mountains, his bow mounted on an attached rack he’d built. He was given orders to be back to his home school co-op science class by 11:00am that morning. “Unless he had a deer down,” said his mother, Aby. “Then I would write him an excuse.”

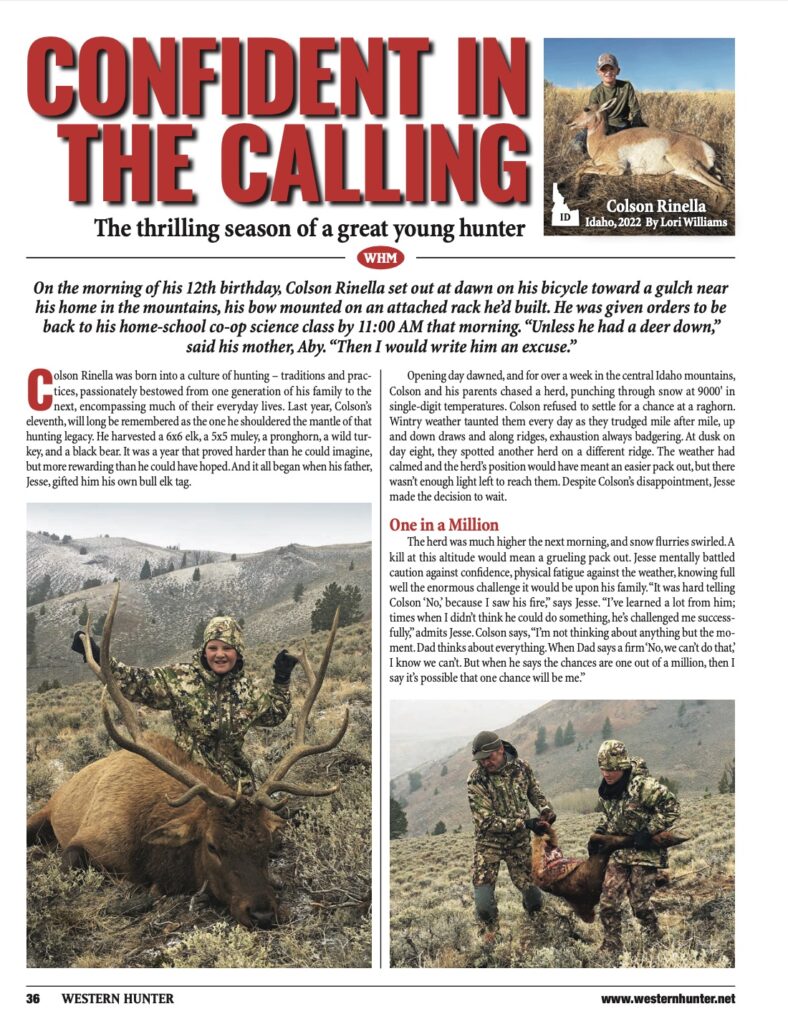

Colson Rinella was born into a culture of hunting – traditions and practices passionately bestowed from one generation of his family to the next, encompassing much of their everyday lives. Last year, Colson’s eleventh, will long be remembered as the one he shouldered the mantle of that hunting legacy. He harvested a 6×6 elk, 5×5 muley, pronghorn, wild turkey, and a black bear. It was a year that proved harder than he could imagine, but more rewarding than he could have hoped. And it all began when his father, Jesse, gifted him his own bull elk tag.

Opening day dawned, and for over a week in the central Idaho mountains, Colson and his parents chased a herd, punching through snow at 9000’ in single digit temperatures. Colson refused to settle for a chance at a raghorn. Wintry weather taunted every day as they trudged mile after mile, up and down draws and along ridges, exhaustion always badgering. At dusk on day eight they spotted another herd on a different ridge. The weather had calmed and the herd’s position would have meant an easier pack out, but there wasn’t enough light left to reach them. Despite Colson’s disappointment, Jesse made the decision to wait.

The herd was much higher the next morning and snow flurries swirled. A kill at this altitude would mean a grueling pack out. Jesse mentally battled caution against confidence, physical fatigue against the weather, knowing full well the enormous challenge it would be upon his family. “It was hard telling Colson no, because I saw his fire,” says Jesse. “I’ve learned a lot from him, times when I didn’t think he could do something and he’s challenged me successfully,” admits Jesse. Colson says, “I’m not thinking about anything but the moment. Dad thinks about everything. When Dad says a firm no, we can’t do that, I know we can’t. But when he says the chances are one out of a million, then I say it’s possible that one chance will be me.”

With one last tearful plea from Colson, who maintained the indecision was wasting time, Jesse and Aby decided to trust him and keep going. It was now early afternoon. Colson pressed his dad higher to the ridgeline. They glassed again, set up the spotter, and Jesse got a bead on one of the larger bulls.

Colson needed 220 yards for a clean hit. As they settled into position the herd stilled and stared their direction. All three froze. When the herd resumed feeding, Jesse ranged one more time and then Colson fired the family’s .243. The 6×6 elk dropped. Tears and snow flurries blurred in the moment Colson says was the happiest of his life.

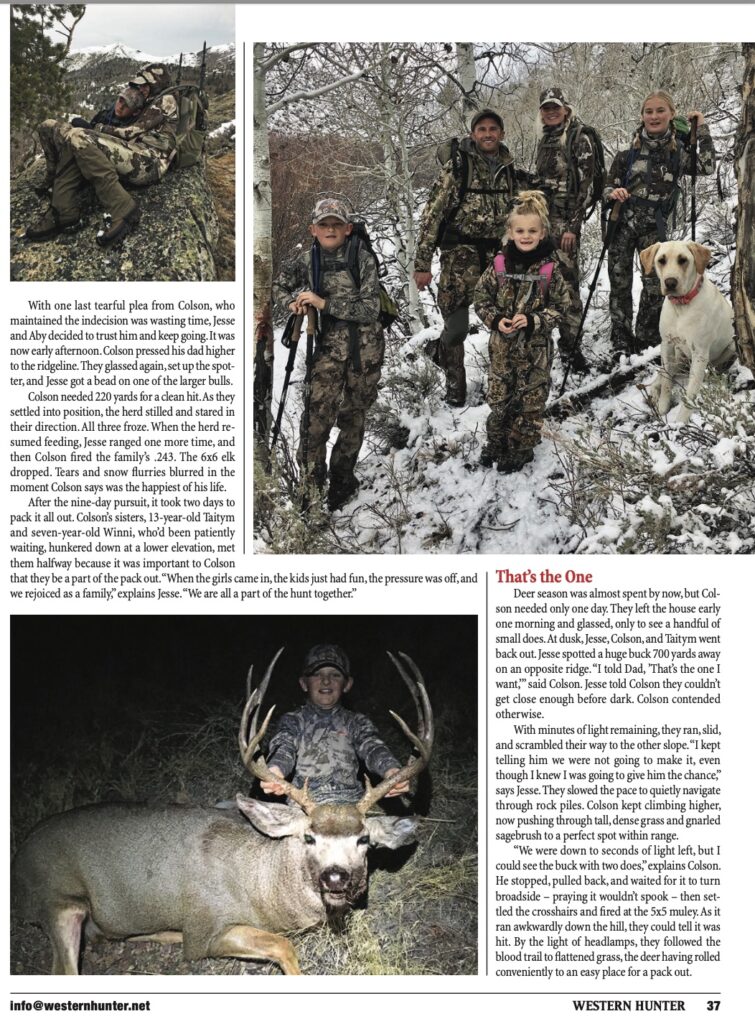

After the 9-day pursuit, it took two days to pack it all out. Colson’s sisters, 13-year-old Taitym, and 7-year-old Winni, who’d been waiting hunkered down at a lower elevation, met them halfway because it was important to Colson that they be a part of the pack out. “When the girls came in, the kids just had fun, the pressure was off, and we rejoiced as a family,” explains Jesse. “We are all a part of the hunt together.”

Deer season was almost spent by now, but Colson needed only one day. They left the house early one morning and glassed, only to see a handful of small does. At dusk, Jesse, Colson, and Taitym went back out. Jesse spotted a huge buck 700 yards away on an opposite ridge. “I told Dad that’s the one I want,” said Colson. Jesse told Colson they couldn’t get close enough before dark. Colson contended otherwise. With minutes of light remaining, they ran, slid, and scrambled their way to the other slope. “I kept telling him we’re not going to make it, even though I knew I was going to give him the chance,” says Jesse. They slowed the pace to quietly navigate through rock piles. Colson kept climbing higher, now pushing through tall, dense grass and gnarled sagebrush to a perfect spot within range.

“We were down to seconds of light left but I could see the buck with two does,” explains Colson. He stopped, pulled back, and waited for itto turn broadside – praying it wouldn’t spook – then settled the crosshairs and fired at the 5×5 muley. As it ran awkwardly down the hill, they could tell it was hit. By the light of headlamps, they followed the blood trail to flattened grass, the deer having rolled conveniently to an easy place for pack out.

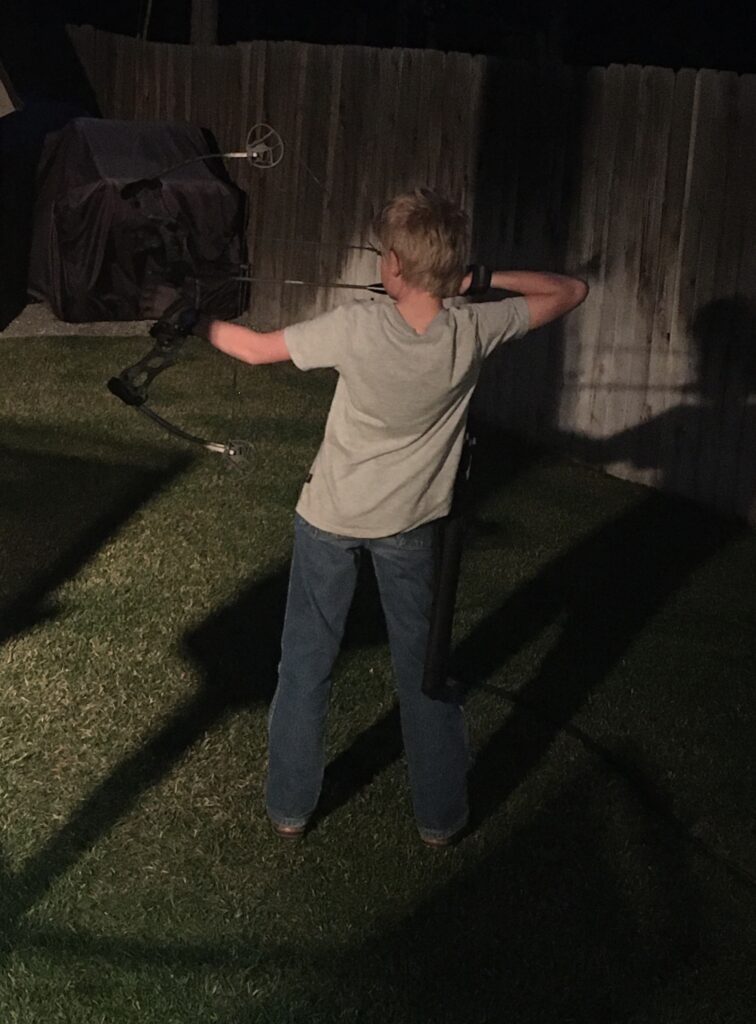

Winter settled in and Colson told Jesse he wanted to shoot a bear with his bow. “I knew the odds weren’t high being able to pull 40 lbs by spring, but if there’s a possibility, I’m going to try it,” says Colson. He began Archery Ed, lifted weights, did pushups, and shot 12 arrows every single day, snow or shine. Jesse may or may not have secretly upped the poundage a few times. When he pulled forty, his focus immediately turned to accuracy.

Spring emerged and the Rinella’s went turkey hunting in April, one of their favorite outings of the year. On a snow flurrying afternoon, Colson called in his tom, then pulled the trigger for a square hit with his grandfather’s 12-gauge shotgun.

Colson was now restless for bear. The first evening out proved uneventful as father and son huddled together in a dirt depression.

“It was really boring,” says Colson. “But I had this feeling we needed to stay because it was possible one would come in. I knew if we went home, we’d just end up watching videos of other people shooting bears.”

As darkness penetrated on the second night, they heard a stick break. Colson readied his bow as they watched a mature male boar amble into view, then turn broadside. “I’d been worried about my nerves in the moment,” admits Colson. “But it just felt like I was shooting at the target in the backyard, which I’d done a thousand times. My arms just raised the bow and it felt easy.” From 20 yards out, he hit the perfect spot at the top of the heart.

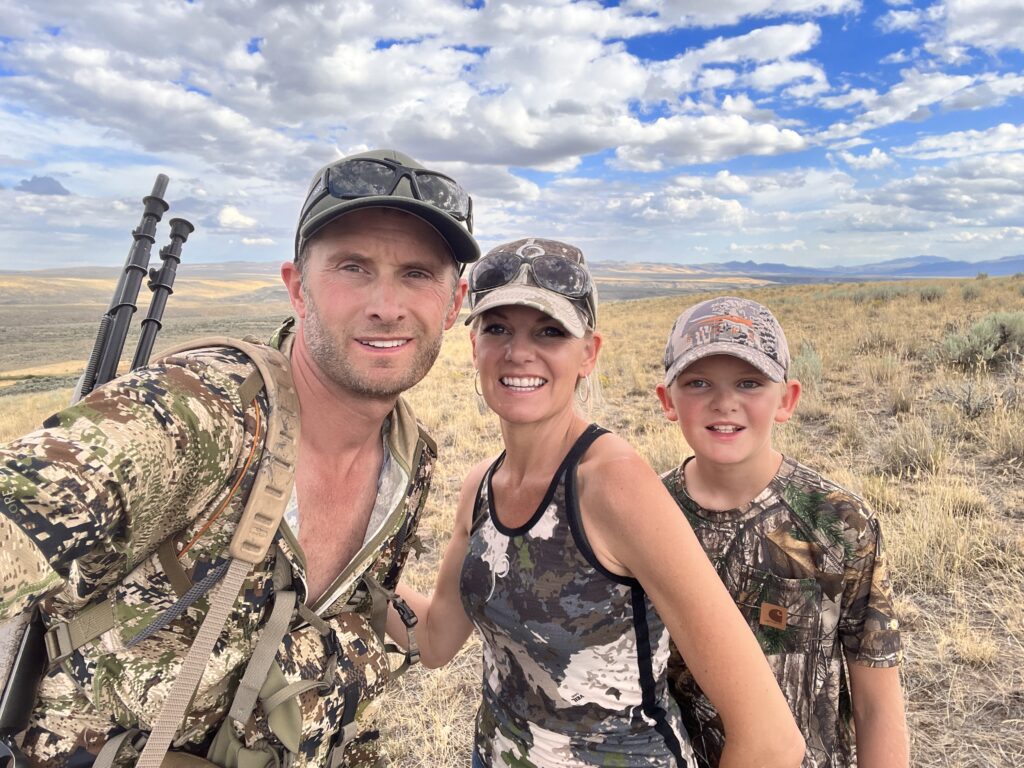

Late summer had the Rinella’s headed for southern Idaho’s vast sagebrush plains for Colson to fill his doe pronghorn tag. In the challenging landscape – a checkerboard of private and public boundaries – Colson anguished over an easy shot at a large doe, because the shot would be questionable. He would pass. The next day, honor and patience rewarded him as he fired the reliable .243 for a sure kill.

Now that Colson is old enough to hunt by himself, forging out on his own has been exhilarating. But hunting is as much about the shared experience as it is filling a tag. Colson has witnessed that truth for all his 12 years. Days after that independent ride at dawn, he loaded up his bike and set out again. It wasn’t long before he returned home to tell his mom, “It feels kind of pointless. There were deer I could have gone after, but it’s just not as fun without you guys.”

**All hunts were Public Land DIY

Lori Williams was born and raised in Idaho. This free-lance writer, copy editor, former home educator, and lover of the mountains enjoys the human interest story and writing poetry.

You can find her on Instagram at @idaho_ethos or www.loriwilliamswriter.com